| Period| | 2022.08.31 - 2022.10.28 |

|---|---|

| Operating hours| | 10:30 - 18:00 |

| Space| | Gallery Meme/Seoul |

| Address| | 3, Insadong 5-gil, Jongno-gu, Seoul, Republic of Korea |

| Closed| | Open throughout the year |

| Price| | Free |

| Phone| | 02-733-8877 |

| Web site| | 홈페이지 바로가기 |

| Artist| |

이기영

|

정보수정요청

|

|

Exhibition Information

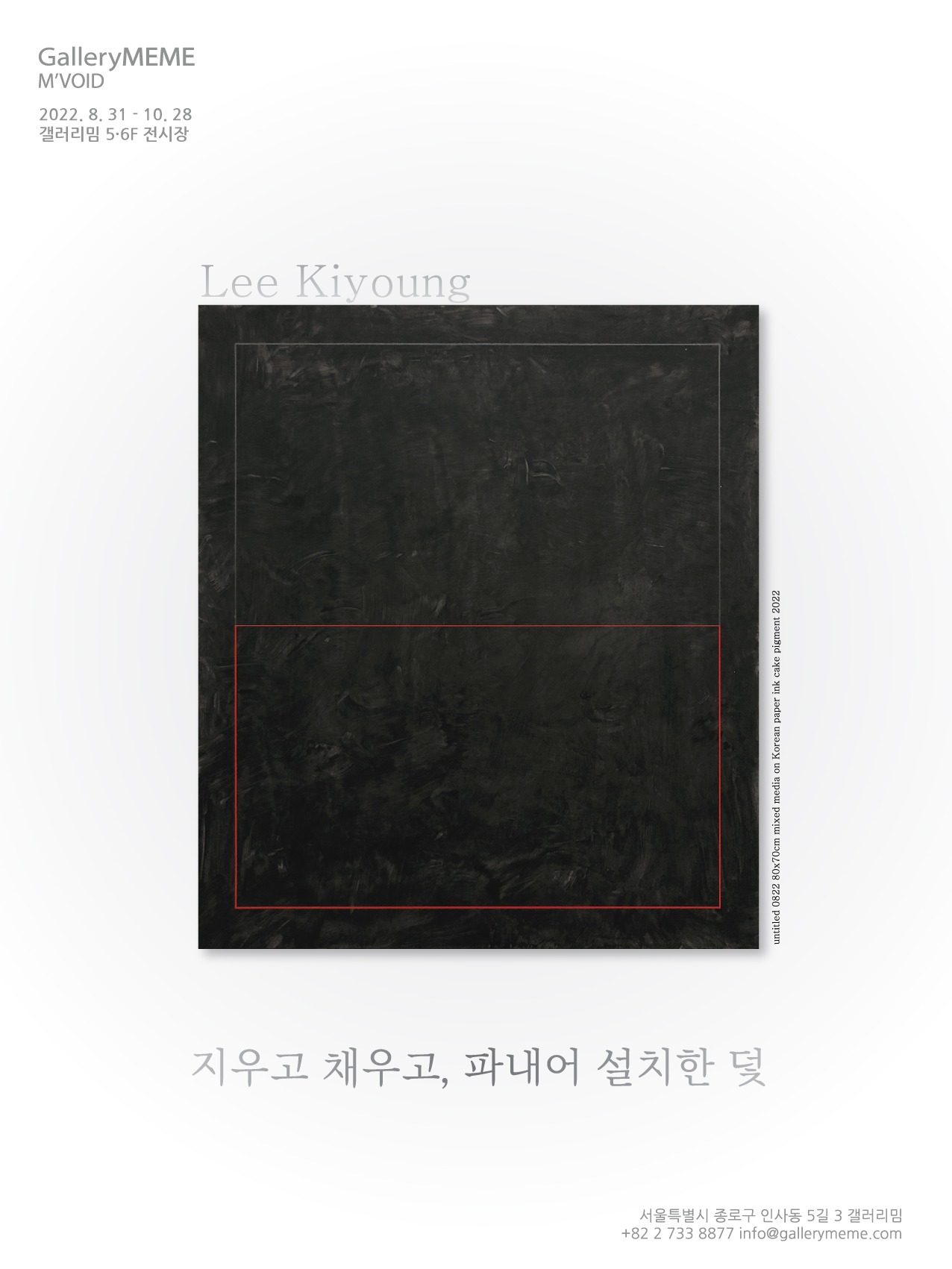

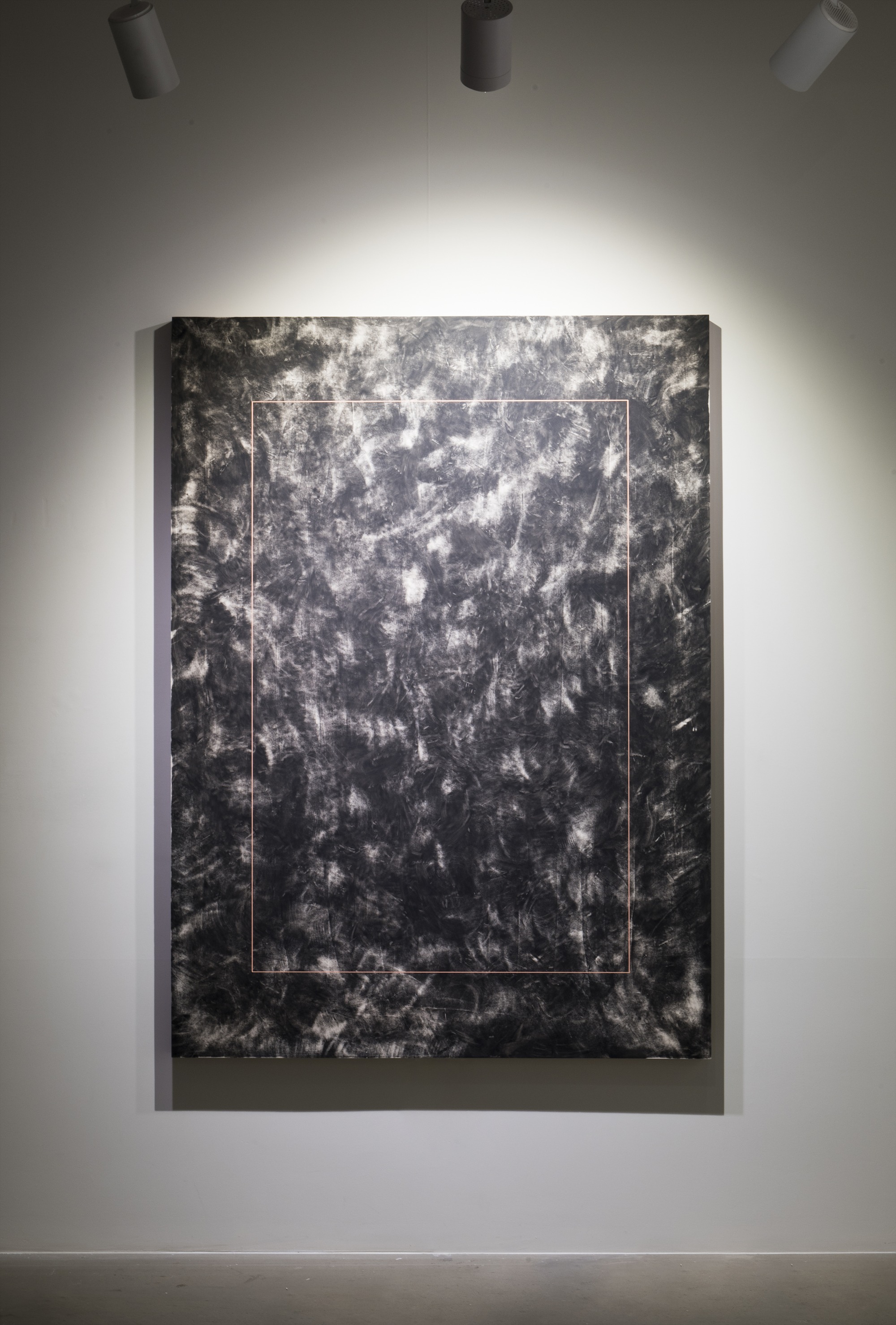

Namsee Kim College of Art & Design, Ewha Womans University In Man and the Seashell, French writer and aesthete Paul Valéry meditates on art with a conch shell in his hand. The dwellings of mollusks with an outer shell of a spiral structure and an inner shell covered with an iridescent layer of mother-of-pearl: how is this beautiful natural object made? Unlike a human product, whose materials should be selected according to an intention to make a specific shape and which must be processed by tools, a seashell grows as the mollusk's flexible body tissues emanate the calcareous components absorbed from the water. While human artifacts are the products of external tasks independent of the task of preserving life, shells are the products of the internal tasks of mollusks to preserve life by absorbing nutrients and water. The spiral-shaped outer crust that rotates clockwise or counterclockwise and the inner crust that “glows in the iridescent light as it receives sunlight and separates the light at each wavelength” are simply the results of the fact that they are alive. Considering that all shells maintain a certain morphological consistency, it is clear that this process is not due to random chance. The different shapes and sizes of shells testify that their formation does not follow any mechanical causality. In this regard, the shell is a product that transcends all human means such as intention, mechanical properties, and contingency. As Valéry points out, humans have an excess of abilities beyond what is necessary to survive. Human beings have feelings of no benefit to themselves, have organs that are not essential to the preservation of life, and have freedom which is frequently detrimental to survival. For a mollusk, whose subsistence is indistinguishable from the formation of a beautiful shell, it is possible to “draw the subject matter of its work from its own substance,” whereas a human being with an excess of ability must produce something "only by the special application of a mind which is separable from the whole of his being." Nevertheless, we want art to embody “a confident production, an inner necessity, a never-dissolving mutual relationship between form and material” like a seashell. We want the lines drawn in a work of art to result from an inner exigency of needing to be drawn only that way, just like the stripes on a seashell. And yet, we do not want them to result from mechanical causality, which binds freedom. For a long time, art has endured the contradictory demand that, although man-made, it must not be arbitrary but necessary and free, and artists have devised their own ways of coping with this self-contradictory overload. Kiyung Lee's method is Kantian in nature. He uses his freedom for self-legislation (Selbstgesetzgebung), imposing rules on himself. Freedom, for him, is exercised for the rules that constrain that very freedom, which govern things that will be erased and disappear. The tension deriving from this runs throughout the entire process of the piece going through a number of transformations from start to finish. The act of filling the surface of jangji (a type of thick, high-quality traditional Korean paper) coated with slaked lime with a name, sentence, or date is unfettered, performed with the knowledge that they will be erased and become invisible later on. To remove these by hand, bamboo brush, or sandpaper is also to evenly fill the surface of the work with Chinese ink. What is dominant in this process of erasing while filling and filling while erasing is the tension between freedom and formality, which intuitively and proactively organizes the accidental visual chaos. The artist compares the tension created by this polarity to “tightrope walking. In the air.” Varnish is applied thirteen times on top of the image as if to fix it at the apex of a tense tightrope. It takes at least ten days since he has to wait for each layer to dry. Then, the painting is placed on an operating table-like workbench for the next, most stressful, process: to carve deep, sharp lines into the varnished layer with a sharp knife. If the knife goes amiss, all the process up to that point will be in vain. The lines, which contain the deep and intense tension thus created, are at first invisible because they are buried in the surface of the painting drawn in Chinese ink. Only after filling the scraped places with bright pigments and grinding the entire surface of the painting with a grinder until it loses its luster do the thin colored lines literally inserted into the picture become visible to the eye. The fine, elaborately carved lines tempt us to take a closer look at the painting by giving a momentary flicker to the overall dark work. Appropriately, the artist compares these lines to "traps" which hide in the picture, making us climb on the "tightrope" and sway in the painting. (Source = Gallery MEME)