| Period| | 2022.09.01 - 2022.10.08 |

|---|---|

| Operating hours| | 11:00 - 19:00 |

| Space| | Tang Contemporary Art/Seoul |

| Address| | |

| Closed| | Sun, Mon *Sun. Reservation Operation |

| Price| | Free |

| Phone| | 02-3445-8889 |

| Web site| | 홈페이지 바로가기 |

| Artist| |

|

정보수정요청

|

|

Exhibition Information

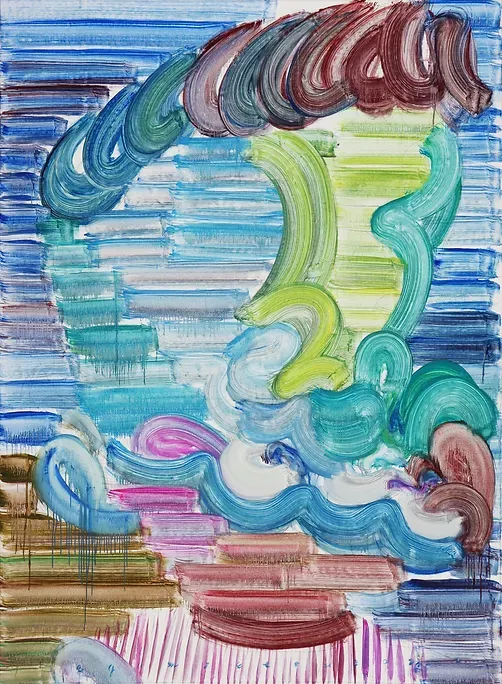

She looked at him, and oh, the weariness to her, of the effort to understand another language, the weariness of hearing him, attending to him, making out who he was, as he stood there fair-bearded and alien, looking at her. She knew something of him, of his eyes. But she could not grasp him. She closed her eyes. ― D.H. Lawrence, The Rainbow (1915) At first glance, the paintings of Etsu Egami might be mistaken for abstract compositions, in which broad brushstrokes summon up discrete horizontal bands of lush, pellucid colour, held in tension with sinuous, almost calligraphic passages. Seen up close, these are works that perhaps above all stress their own materiality – witness how the fibres of the artist’s brush rake through her paints, how chemistry and gravity conspire to make an upper band of pigment bleed into a lower, how the primed canvas peeks through the gaps between her marks, as though to remind us that each of these images is also an object, a physical meeting of a medium and its support. And yet, step back from these paintings, give them a little space to breath, and we see something altogether different. Human faces begin to emerge from the brushstrokes, abstraction birthing figuration, distance creating, if not exactly clarity, then at the very least an enriched data set. Etsu Egami is fascinated with communication, and its inherent limits and lacunae. Born and raised in Japan, trained in China and Germany, and now exhibiting across the world, she exemplifies the international background and outlook of the third generation of post-war Japanese contemporary artists. Her existence at the intersection of multiple languages and cultures has given her a keen sense of how mutual comprehension often founders on the rocks of difference. As she has related: “Living in a foreign country, the very first thing one would encounter is the communication barrier […] It causes laughter and leaves the speaker distressed and tormented in a gloomy grey area”. At the most fundamental level, I suspect her practice is informed by what Western philosophers commonly describe as the ‘problem of other minds’ – that is, the intractable fact that we can only know other people through their outward expressions (or more precisely through our contingent perceptions of those expressions), which can ultimately lead us to doubt the reality of any consciousness save our own. Perhaps this is why she has said that ‘humans communicate with each other, not to get close, but rather to evaluate their distances’. If every act of communication is to some degree necessarily an act of miscommunication, then the gap between one mind and another will never be closed. Still, we live in a world of signals, and few things blink more urgently on the faulty radar of our brains than a human face. Indeed, there is whole sector of our cerebral cortex, the fusiform gyrus, dedicated to facial recognition, which activates differently depending on whether we are a social butterfly, or a shy, shrinking violet. Gestalt psychologists contend that our predisposition to seek out faces amid the ceaseless mass of visual information that the world throws at us is rooted in parent-infant attraction, a process whereby parents and infants form an internal representation of each other, thus reducing the chance that a mother or father will abandon their newborn due to recognition failure. Perhaps this is why our brains are vulnerable to pareidolia, a cognitive tendency to perceive facial features in the most nebulous of visual stimuli, which leads us to detect a wink and a smile in an emoji formed from a semi-colon and a right parenthesis, or a human visage in the shadows on the surface of the moon. Looking at Etsu Egami’s paintings, with their emerging countenances, we might at first wonder whether we are experiencing something similar. The artist, of course, is responsible for depicting the faces in her paintings, yet the fact that we must work a little to see them – move away from the canvas, mentally fix a sweep of semi-autonomous pigment into the form of an eye or ear – makes us somehow implicated in their creation. Could this be why Etsu Egami has reported that on encountering these images, some viewers are convinced that they recognize the face of a person they know? What we perceive as reality always cleaves to the particular investments of our psyches, and this is what makes authentic communication – and durable consensus – so very difficult. We might note in passing that when Etsu Egami has run her paintings under the disinterested eyes of facial recognition software, it has been unable to detect any evidence of a human countenance. It almost goes without saying that the face is by far the most expressive part of the human body. It is the locus of speech, yes, but also of a welter of non-verbal communication – the raised eyebrow, the crooked grin, the tear streaking down a cheek. Nevertheless, we can never quite trust that these are an exterior manifestation of an interior truth – as William Shakespeare memorably put it in his play Macbeth: “There’s no art / to find the mind’s construction on the face”. Maybe it is only the very young, those as yet unschooled in the social necessity of sometimes concealing their emotions, who present a truly honest visage to the world, and this makes the fact that many of Etsu Egami’s recent paintings feature the faces of infants (including, significantly, her own self-portrait) all the more intriguing. All chubby cheeks and bulbous foreheads, little beings of this age connect with the world not through a particular mother tongue, freighted with centuries of cultural assumptions, but rather through instinctual, and perhaps universal, pre-verbal communicative gambits – a cry of distress, a laugh of delight, a hand stretched out towards an object of desire. This does not, we should note, make their inner reality wholly knowable to adults. Looking at Etsu Egami’s paintings, we’re confronted with a series of gnomic countenances, behind which tiny, growing minds make their first reckonings with existence. This is a stage of life most of us recall, if ever, only in brief flashes, and even these are filtered through the gauze of language, and of all the knowledge and experience acquired in our later years – as Marcel Proust famously observed: “the remembrance of things past is not necessarily the remembrance of things as they were”. It’s a testament to the artist’s rare insight into the strange contours of our shared humanity that she can make these infants feel at once so familiar, so precious and so stubbornly alien. Etsu Egami’s use of translucent colour is by any measure remarkable, combining an insistence on the liquid substance of her pigments, and the way they respond to the graceful slashes and arcs of her brush, with a sense that she is painting not with oils, but with something closer to light. Her palette might best be described as a slightly grubby rainbow, as though that miraculous, sky-strafing natural phenomenon had fallen to Earth, and in the process become soiled, whilst still remaining thrillingly chromatic. (I’m reminded that the Japanese Tango no kuni Fudoki relates how the Floating Bridge of Heaven, which took the form of a rainbow, eventually collapsed, forming the lands west of Kyoto). In several cultural traditions, rainbows represents the connection between the human and the numinous, suggesting a path from our limited perspective to a vision of a deeper reality. Norse mythology tells of the Bifröst, a shimmering prismatic crossing linking the Earthly realm to Asgard, home of the gods. Tibetan Buddhism teaches that those who reach the last stage of spiritual development before achieving Nirvana find their flesh transformed into a ‘rainbow body’. For followers of the Abrahamic faiths, the rainbow is proof of humanity’s redemption, and a guarantee of its future ascent towards the divine. There is an echo of this trope in Etsu Egami’s claim that for her, this meteorological spectacle is “a symbol of dream and hope”. Can such abstractions really be embodied not in geometrically perfect bands of pure, unblemished colour, but rather in uneven, faintly muddied swoops of pigment? We should remember that hopes and dreams are not only imaginative projections of a better future, but also a testament to the deficiencies of the world we currently inhabit. Perhaps this is why the artist’s rainbows feel like they have absorbed something of the ground beneath our feet. If pathos is an important element in Etsu Egami’s paintings, then it is balanced, if not by utopian dreams and hopes, then by a modest, cautious optimism. She has related that while human connections are fraught with ‘distance and uncertainty’, recognizing that this is not a bug, but a feature, has allowed her to ‘vaguely see the rainbow in the gray area of communication’, and it is this we glimpse emerging in her most recent canvases. To commune with the faces in her paintings is not to commune with another person, but rather with our own (deeply human) perspectival habits and limits – something we all possess, something that causes us all loneliness and pain, and something we’re all too often persuaded to forget. (Source = Tang Contemporary Art)