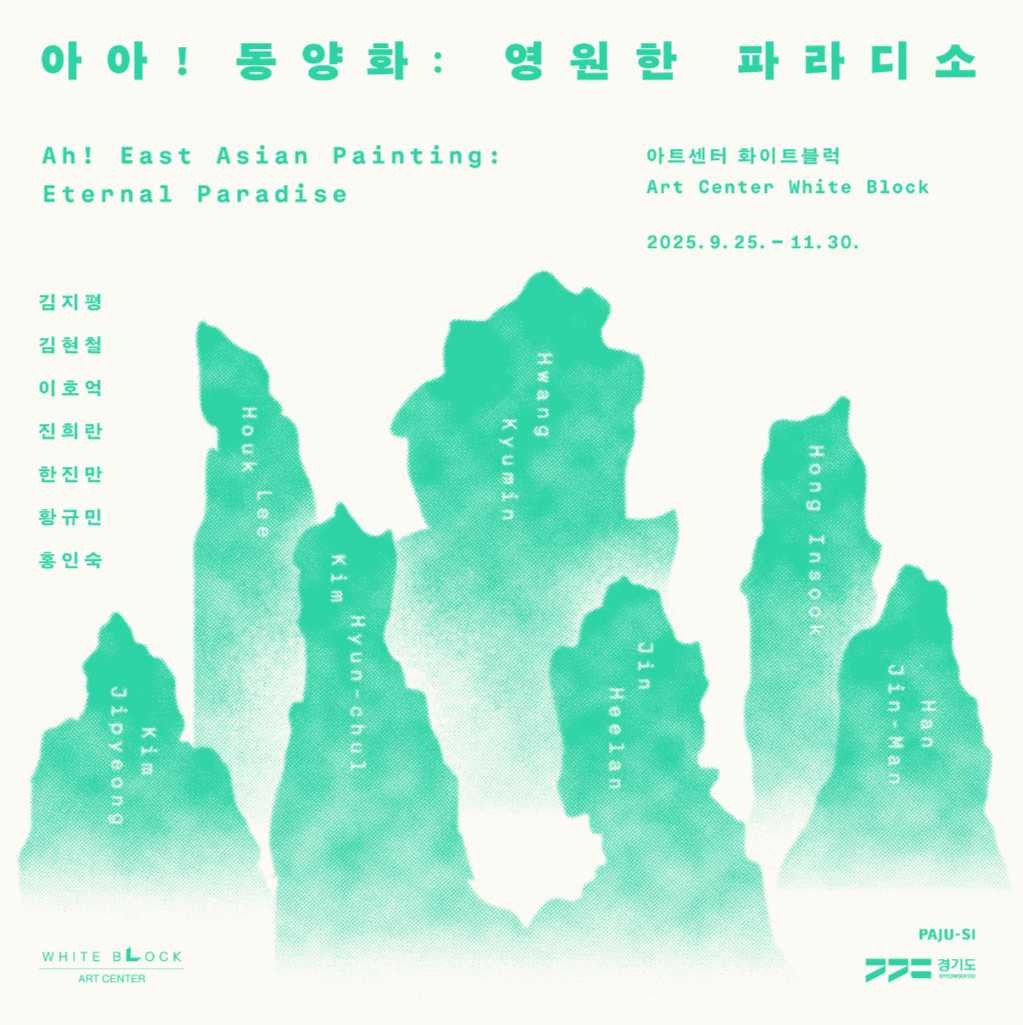

| Period| | 2025.09.25 - 2025.11.30 |

|---|---|

| Operating hours| | 11:00 - 18:30 |

| Space| | Art Center Whiteblock |

| Address| | 72, Heyrimaeul-gil, Tanhyeon-myeon, Paju-si, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea |

| Closed| | Open throughout the year |

| Price| | |

| Phone| | 031-992-4400 |

| Web site| | 홈페이지 바로가기 |

| Artist| |

진희란,홍인숙

|

정보수정요청

|

|

Exhibition Information

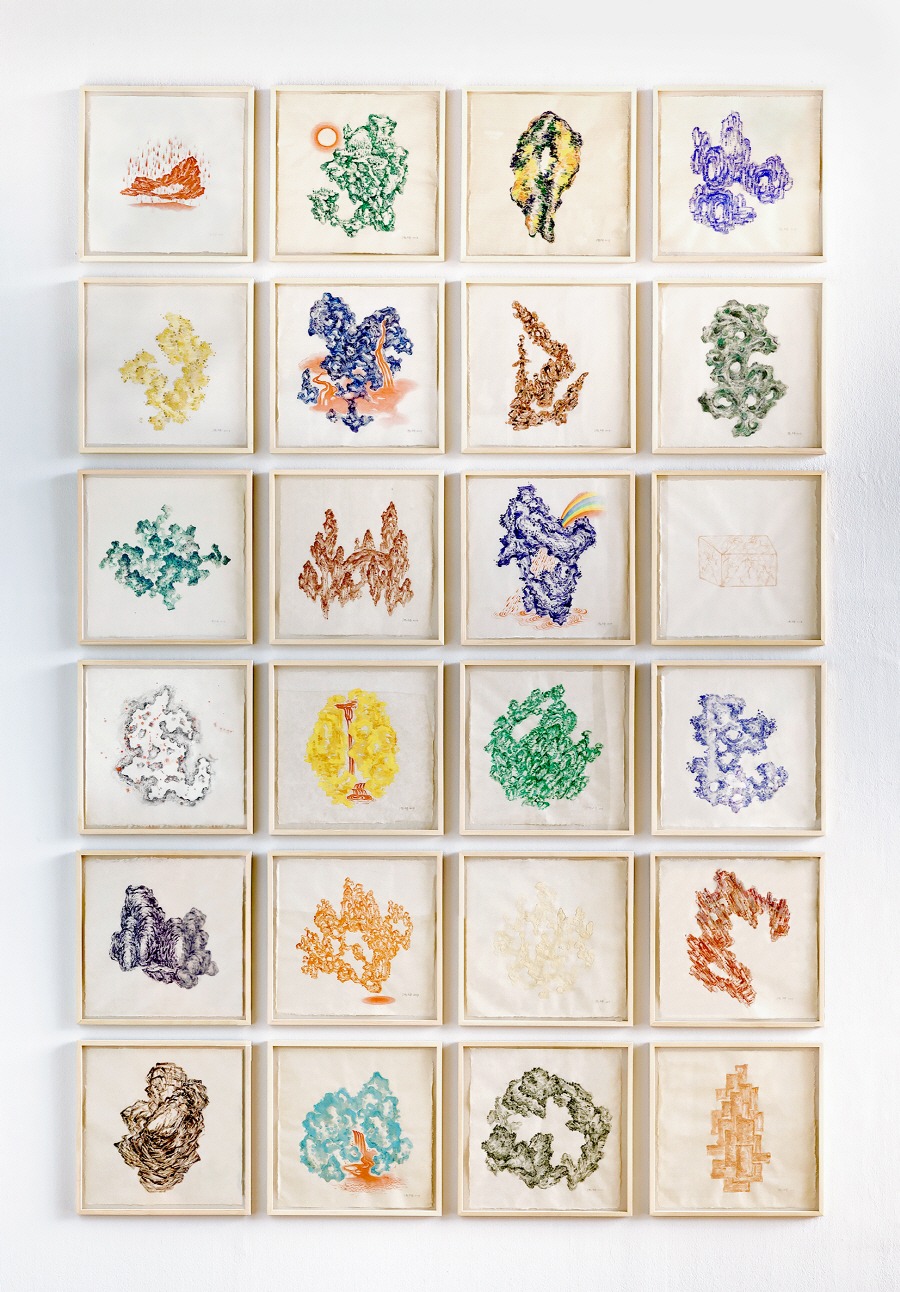

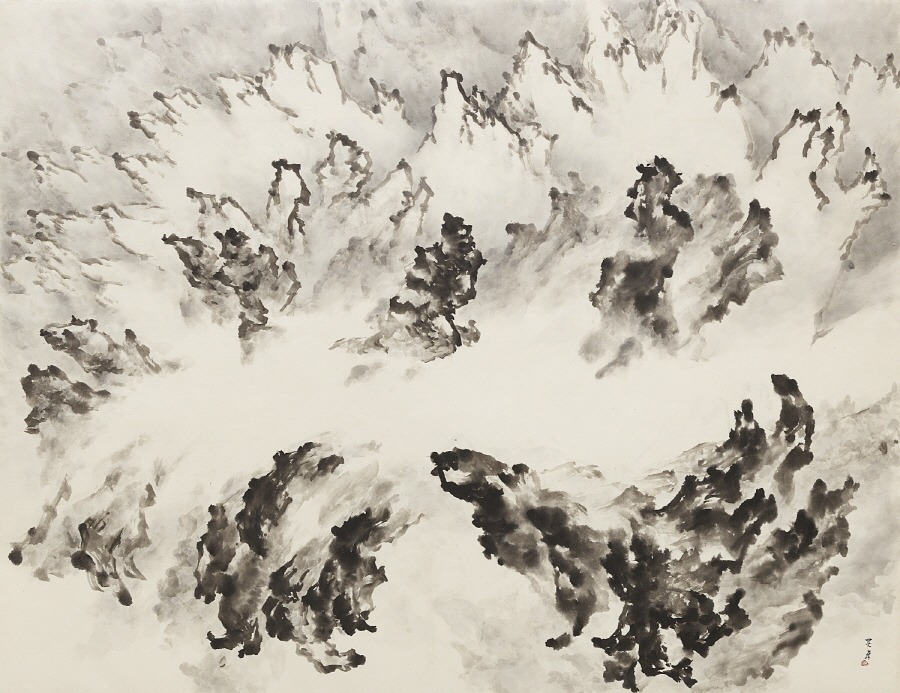

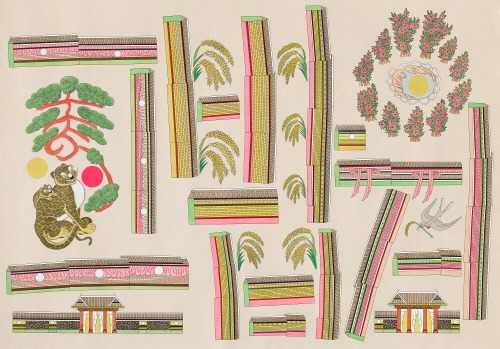

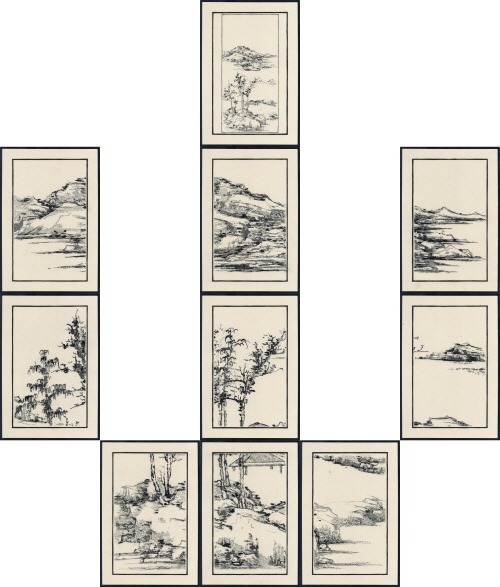

Ah! East Asian Painting: Eternal Paradise The Art Center White Block presents Eternal Paradise, the fourth and final chapter of the four-episode exhibition series Ah! East Asian Painting. With this exhibition, the journey that has unfolded over the past four years comes to its close. The fourth exhibition turns its gaze toward the tradition of East Asian painting. Once regarded as central, this tradition later came under criticism for its perceived inability to respond to the transformations of modernity. Eternal Paradise brings together artists who appropriate and re-imagine this very notion of traditional painting. What do these artists understand as tradition, and what stories do they seek to share with the world through it? Why does landscape painting remain sustainable for both the present and the future, and why does folk painting continue to hold significance as art today? In portraiture, how is the principle of Spirit Resonance (傳神) embodied in contemporary practice, and in what ways do the artists interpret the relationship between tradition and the present? It is through such questions and responses that this exhibition takes shape. In Eternal Paradise, seven artists delve deeply into tradition, uncovering anew the present within its depths. This exhibition centers on their artistic perspectives while illuminating the timeless value of art that transcends eras. Through varied reimaginings of traditional painting—its surfaces and concepts expressed in ink, brush, color, and tonalities of heritage—it invites viewers to perceive both the divergences and affinities across generations. The four-episode exhibition series Ah! East Asian Painting has charted a course distinct from previous presentations of East Asian painting in Korean society. Earlier exhibitions largely arranged artists chronologically, a method well suited to providing an overview of the flow of East Asian painting within Korea. Today, however, the urgent issues lie in the very survival of East Asian painting and its transition into the language of contemporary art. At such a moment, what is needed is not a survey, but the shaping of discourse. Thus, Ah! East Asian Painting sought to reveal the present state of East Asian painting through a multiplicity of perspectives. Conceived under these conditions, the four-episode exhibition series expose the points of conflict that East Asian painting has encountered within Korean society, while also tracing how the medium has been compelled to transform in pursuit of a renewed artistic order. The points of conflict embody the traces of tension between tradition and modernity, between the old and the new, and mark the very site where East Asian painting continues to collide vigorously with contemporary art. Today, younger painters are less preoccupied with the “spirituality of ink” than with rendering, upon the pictorial surface, worlds intimately bound to their own lives. The once-rigorous use of brush, ink, and paper has now expanded into a wide spectrum of painterly materials. Yet not everything must change. The succession and evolution of tradition remain essential. Tradition is both a luminous cultural heritage and a foundation that sustains the diversity of artistic culture. And if we recognize that art, at its core, embodies an aesthetics of distinction, then traditional East Asian painting must be regarded as an invaluable form that must not vanish from the history of art. The gaze of external viewers toward East Asian painting must also evolve. Before anything else, we must ask by what standards we perceive its transformation. Korean East Asian painting today is moving steadily toward the realm of contemporary art. Thus, the predisposition to interpret it solely through the lens of the past should be set aside. To truly understand the perspectives, concerns, and transitions of artists who live and create in step with the changing times, we must cultivate broader vision and deeper inclusivity. At this juncture, East Asian painting deserves attention not as a matter of “definition,” but as a matter of “expansion.” Let me then highlight a few distinctive qualities of East Asian painting. First, it reveals a striking difference from Western painting in its representational system. Whereas Western painting maintains a distance between the subject and the artist, East Asian painting dissolves that distance through an attitude of unity between self and object. Second, it embraces multiple perspectives, rooted in a non-linear, non-perspectival mode of vision. Third, it perceives form through the discipline of line drawing. Fourth, it cultivates openness through the use of Yeobaek (the aesthetic of the blank), leaving space as a site of possibility. Fifth, it sustains flatness by forgoing the depiction of shadows. Sixth, it allows image and text to coexist within a single pictorial plane. Beyond these, East Asian painting encompasses a wide range of formal particularities that together constitute an aesthetic distinct from other artistic traditions. It is now necessary to reconsider the notion of the “True-View Landscape (眞景).” The emergence of this concept can be traced back to the late Joseon Dynasty, when Gang Se-hwang (pen name: Pyoam) employed the term “Dongguk Jingyeong (True-View Landscapes of Korea, 東國眞景).” At this point, we must ask anew: what prompted Pyoam to coin the expression Dongguk Jingyeong? After all, the practice of depicting the “Actual Landscape (實景)”—that is, the rendering of real scenery—had already been a familiar mode within the broader tradition of East Asian landscape painting. In China as well, numerous landscape paintings were grounded in the observation of actual scenery. The great masters of earlier times, who had studied East Asian painting within the Chinese cultural sphere, often learned through celebrated works and influential manuals such as The Ten Bamboo Studio Manual of Painting (十竹齋畵譜), The Gu Family Painting Manual (Gossi Hwabo, 顧氏畵譜), and The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting (Gyejawon Hwabo, 芥子園畵譜). Yet what Pyoam referred to as True-View Landscape was not identical to a simple Actual Landscape. True-View Landscape was the act of recognizing the beauty of the very mountains and streams before one’s eyes, of the changing seasons, and of the familiar scenery of one’s own village—and of rendering these scenes onto the pictorial plane as an expression of the nation’s sentiment. What, then, was Pyoam seeking to convey in bringing forth the notion of “the True (眞)”? True-View Landscape was not a mere recording of scenery; it marked, rather, a “recovery of subjectivity”—an awakening to the beauty of the immediate landscape, free at last from the shadow of China. Without this subjective gaze, even an Actual Landscape could not attain the status of a True-View Landscape. Thus was the True-View Landscape born: to capture the beauty before one’s eyes, to depict the world as one has truly seen it—this was both a recovery of subjectivity and the very essence of True-View. And this essence, in turn, resonates with the essence of art itself. Perhaps Pyoam’s intuition had already penetrated this truth. In today’s art world, where no fixed entity or meaning can be said to exist, the reason for curating this exhibition was to reveal, without concealment, the very state of confusion that surrounds East Asian painting. One might question whether exposing such disarray could ever serve as a resolution; yet there seemed to be no alternative but to present reality as it is. It was in this spirit that Ah! East Asian Painting was conceived as a four-episode exhibition series. Episode I, Rhapsody of East Asian Painting, featured artists who majored in East Asian painting yet chose not to practice it. Episode II, Already·Always·Everchanging, brought together artists trained in East Asian painting but working in forms divergent from its established order. Episode III, Dongyanghua, One and All, presented artists without a background in East Asian painting, yet engaged in a dialogue with it through influence and resonance. Episode IV, Eternal Paradise, was devoted to artists who continue the tradition of East Asian painting. Together, these four episodes collided and intersected, revealing the diverse topographies of East Asian painting. And so I came to a realization: that beyond this period of confusion, we may come to encounter a more mature form of contemporary East Asian painting and a transformed artistic culture. With this expectation, I bring to a close the four-year journey and share these reflections. Lee Jeong Bae