| Period| | 2026.01.21 - 2026.03.07 |

|---|---|

| Operating hours| | 10:00-18:00 |

| Space| | White Cube/SEOUL |

| Address| | 6, Dosan-daero 45-gil, Gangnam-gu, Seoul, Korea |

| Closed| | Sun,Mon,Wed |

| Price| | Free |

| Phone| | 02-6438-9093 |

| Web site| | 홈페이지 바로가기 |

| Artist| |

에텔 아드난

|

정보수정요청

|

|

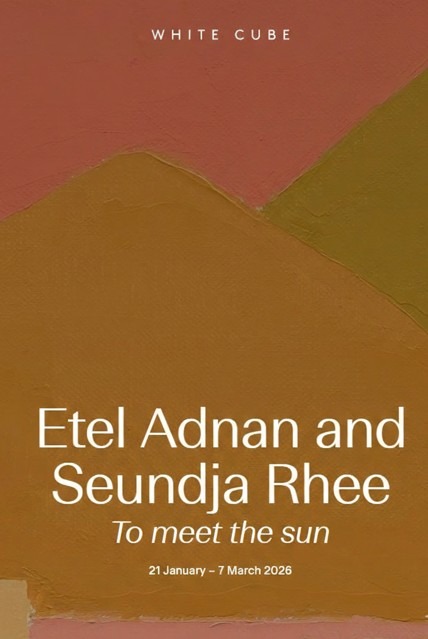

Exhibition Information

Presenting the work of Lebanese artist Etel Adnan (1925–2021) and South Korean artist Seundja Rhee (1918–2009), ‘To meet the sun’ at White Cube Seoul brings into correspondence two practices shaped by migration, exile and the pursuit of artistic form far from home. Though marked by different geopolitical conditions, their trajectories disclose notable affinities: both were drawn to Paris and turned to painting in adulthood without prior formal training. Each, in turn, developed a distinctive visual vocabulary informed by abstraction, philosophical enquiry and the era’s expanding fascination with space exploration in the 1960s. It was within this milieu that Adnan wrote the 1968 leporello poem from which the exhibition takes its title – an elegy for humanity’s first cosmonaut that finds an echo in Rhee’s own evolving cosmological investigations. Across their practices, recurring motifs anchor shared meditations: for Adnan, suns, moons and the silhouette of Mount Tamalpais; for Rhee, geometric configurations that index the structures of Earth and planetary systems. Read less Both artists came to painting in their thirties, albeit under markedly different circumstances. Rhee’s relocation to France in 1951, amid the Korean War, entailed a profound rupture: forcibly separated from her three young sons, who remained in the care of her ex-husband, she arrived in Paris having to negotiate personal estrangement and the male-dominated climate of postwar abstraction. Enrolling at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière in 1953, she embarked on a committed study of Western modernism that would, over the decades, develop into a succession of distinct stylistic periods. During her early years in Paris, Rhee cultivated an abstract vocabulary shaped by her studies under Henri Goetz, whose Surrealist-inflected pedagogy – with its attentiveness to both cosmic and unconscious terrains – proved formative. Following an initial foray into figuration, her earlier, more resolved brushwork dispersed into constellations of small, deliberate strokes and layered chromatic planes in which surface and gesture supersede depiction. The paintings she produced in the late 1950s register this transition: their glyphic geometric forms and textured grounds speak obliquely to memories of her homeland and to the condition of motherhood. Developed between 1961 and 1968, her subsequent ‘Woman and Earth’ period marks Rhee’s formulation of an abstraction in the relationship she identified between womanhood and land. Her granular, alternating strokes accumulate into densely worked surfaces that critics have likened to cultivated earth and traditional hwamunseok weaves, aligning her pictorial language with materials and processes historically associated with women’s labour. Adnan’s route to Paris was more circuitous. She first travelled to the French capital as a young student of philosophy at the Sorbonne, long before she conceived of herself as an artist. It was only later, while living and teaching in California, that she began to experiment with colour and gesture, shaped by the light of the American West, as well as the immediacy of working at speed with unmixed pigments. She returned to Beirut in the early 1970s, entering an energetic artistic and literary milieu that would inform her exhibitions and writings of that time. The outbreak of the civil war in Lebanon, however, propelled her into another period of movement – this time an exile she would describe as ‘absolute’, in which ‘all living symbols of one’s identity’ are violently lost.2 When she eventually settled in Paris decades later, this experience of rupture would find home in a refined, abstract language through which memory, landscape and metaphysical thought could be held. Rendered in swathes of pure pigment applied directly onto a pre-stretched canvas laid flat upon the table, Adnan’s paintings are intimate in scale and charged with feeling. Viewed from afar, her works register the world beyond, stitched together from blocks and bands of vivid colour and suffused with tranquil light. Her turn to tapestry later in the 1960s extended this chromatic vocabulary into a slower, tactile medium. She began experimenting with hand-woven techniques while living in California, and would later collaborate with the artisans of Atelier Pinton to realise compositions in which the pared-down geometries of her paintings unfold into more intricate – and at times more agitated – contours of terrain. Rhee’s travel to the cosmopolitan metropolis of New York in 1969 sharpened a spatial intuition already nascent in her ‘Woman and Earth’ paintings, whose grounded orientation nonetheless anticipates a more expansive conception of pictorial space. In these works, elemental forms – lines, squares, circles – emerge subtly, functioning as indices of body and terrain while simultaneously operating as interrelated components within a broader spatial order that begins to gesture beyond a fixed, earthbound vantage. Held in a state of balance and tension, these configurations mark the early formation of Rhee’s search for equilibrium across opposing forces and cultural inheritances, prefiguring an investigatory arc that would later orient her practice towards increasingly expansive horizons. The Moon missions of the 1960s, and the new planetary perspectives they inaugurated, proved generative for both artists. For Adnan, the era’s expanding cosmological imagination entered her work directly, informing a body of writing and guiding her paintings and tapestries towards increasingly celestial forms. Circular shapes and suspended, pixel-like squares – evoking suns and moons – appear with new insistence, while concentrated planes of colour flatten the pictorial field and reduce horizons into tonal bands. While she continued to look to landscape, devotedly painting the profile of Mount Tamalpais, the compositions that emerged in the aftermath of this period evidence a new outlook. In her tapestries, the horizon recedes entirely, supplanted by free-form patchworked fields whose spatial logic alludes to geographical borders only to exceed them. For Rhee, the same period laid the conceptual ground upon which her later ‘Cosmos’ (1995–2008) works would emerge, extending her artistic enquiry from Earth to city to sky, before, finally, reaching the astronomical realm. 1 Etel Adnan, A Funeral March for the First Cosmonaut, 1968, accordion book, with pen and ink and watercolour on paper, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York 2 Etel Adnan, ‘Voyage, War and Exile’, Al-‘Arabiyya, vol.28, 1995, p.8