| Period| | 2019.10.31 - 2019.11.24 |

|---|---|

| Operating hours| | 12:00 - 18:00 |

| Space| | Artspace Boan 1942(Boan1942)/Seoul |

| Address| | 33 Hyojaro, Jongrogu, Seoul, SouthKorea |

| Closed| | Monday |

| Price| | Free |

| Phone| | 02-720-8409 |

| Web site| | 홈페이지 바로가기 |

| Artist| |

|

정보수정요청

|

|

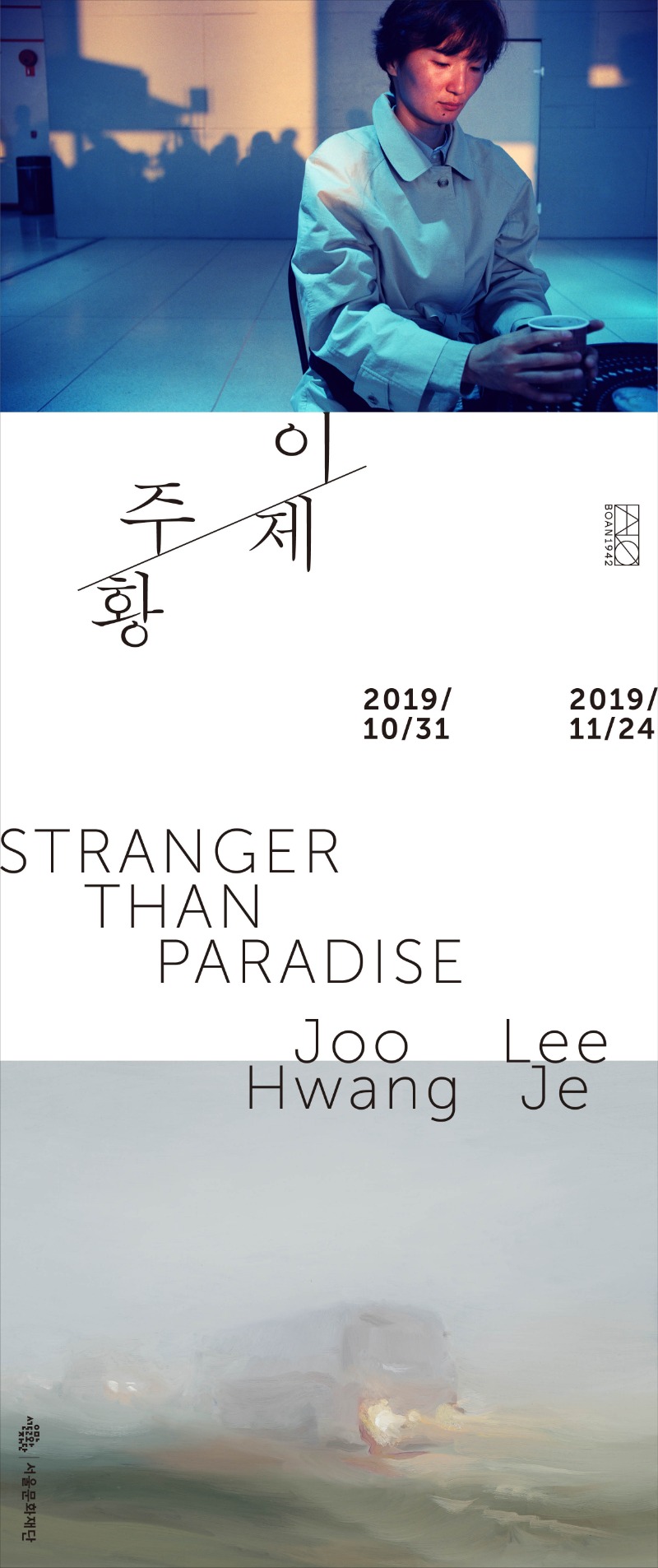

Exhibition Information

Stranger than Paradise is a duo show by Joo Hwang, photographer and Lee Je, painter. The two artists differ not only in their artistic media but also in their generation and background, yet have been in close dialogue on the fascination and power of each medium, out of curiosity and respect for each other’s practice. Neither Joo’s work nor Lee’s distinctively emphasize female representation or the representation of femininity; or focus on topics of feminism. However, if one would point out any fundamental core connecting both practices, it would be their ardent endeavor to pursue a possible portraiture, landscape and affect of contemporary women’s life. In her recent work, Joo Hwang dealt with the cultural discrepancies and layered temporalities that construct female identity through pristine photography. Whereas Liking What You See ( 2016) series investigates the mechanism operating identity and fantasy around South Korean women through the aesthetic of so-called K-Beauty, Minyo, There and Here (2018) highlights the presence of Korean women in diaspora in Primorsky region and Japan. Since her solo exhibition in 2005, Lee Je has been depicting female body or shape as a place imprinted with social and symbolic signs and as ever-transforming organism on her canvas. The female ‘becoming’ in her painting includes portraits of girls, breasts, pottery, heat, dances and communities. Appearing as a rhythm and a dynamic territory, these motifs aren’t confined to their figurative shapes. In their artistic practices, the female issues unfold neither as a solid urge to speak nor as autobiographical projection. Joo, a serious aerophobe, photographed women she first met in airport, while Lee painted portraits of young girls in solitary wind after the tragedy of Sewol Ferry. In both works, the shapes of women are rather distant beings that they haven’t yet spoken to, even though the artists identify as women themselves. In their works, accompanied by conscious listening to experiences and times that differ from their own, female portraiture always appears as faces that are familiar yet cannot be remembered or as like a multitude that cannot be labeled with any specific identity. In this exhibition, the two artists unravel their stories about female portraiture as differing memories and objects on each account. During last summer, Lee traveled along the Tumen River by herself, visiting the cities of Tumen, Hunchun, Ussuriysk and Vladivostok. The goal was to physically experience and convey the lives and landscapes of people who were supposed to be totally different from ‘us’ or have been considered to be a part of ‘our’ ethnicity, rather than passively listening to their stories. Joo, on the other hand, reopened her photographs from an older time when she studied in New York, as she felt to have lived ‘most foreign’ in a society. The photographs show portraits of people she met back in 1996 in East Village where it used be temporary base for immigrants, people of color, students and broke artists. These portraits convey the daily life of ‘us,’ subjected to the external gaze as ‘the other.’ In these objects, figures and landscapes framed by means of camera and canvas, the female subject is not a category that divides and competes among ethnicities, generations, origins and class based on gender identities. Instead, it is allegories of unfamiliarity and nonidentity, constantly confronted by people with unstable and uncertain future. They are portraits, landscapes, gazes and echoing responses of people who can be neither easily defined nor identified, of the ones who cross the border and who are always on departure. In Jim Jarmusch’s road movie Stranger than Paradise, Willie and Eddie, who live in a slum in New York City, decide to leave for Cleveland to visit Eva, Willie’s cousin. Reaching Cleveland for the first time, Eddie says to Willie: “Isn’t it funny? We arrive to a new place but everything is all the same.” That happens again when they ‘kidnap’ bored Eva, who’s been only commuting between home and the hot dog place where she works. They head to Florida, the so-called paradise. The stranger who escaped home in search for dream yet gets trapped again in mundane everyday. For the mediocre youth, both picturesque scenery and the wind in paradise appear just arid and boring. There, no familiar place and nobody seeking for me exist, neither in Budapest, New York nor in Cleveland and not even in Florida. To leave for somewhere unknown would be always exciting to someone, inevitable to someone else and even dreadful to others. It won’t simply depend on the taste or the personality fond of leaving, but on the intensity and gravity how instable or affined one is under a circumstance of departure. In contrast to brief trips escaping from the restrictions of daily life, on a solitary journey toward somewhere unknown, tension dominates the traveller from head to toe. For the ones who have to migrate to a foreign country to support the survival of family regardless of approaching hardships or the ones who have to cross the ocean desperately for survival, departure means to confront with extreme xenophobia and to endure the degradation of their existence as ‘the unnecessary other.’ The emotion of the alienation that varies according to each subject, the incomparable tranquility, unfamiliarity and the sense of terror––could these be the time and space of what we call ‘migration’? Anyhow, in our era where the mobility of diaspora, migration and travel is practiced as life necessity than individual motivation, women in the world are always on departure and a stranger everywhere. Even in their own towns and homes.