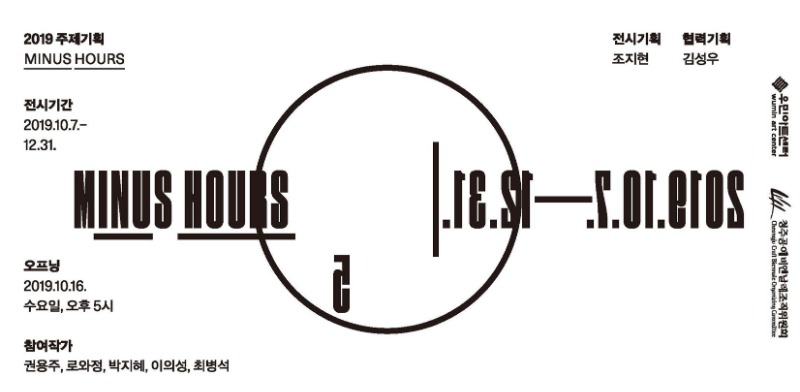

| Period| | 2019.10.07 - 2019.12.31 |

|---|---|

| Operating hours| | 10:00-18:00 |

| Space| | Wumin Art Center/Chungcung |

| Address| | 164, Sabuk-ro, Sangdang-gu, Cheongju-si, Chungcheongbuk-do, Republic of Korea |

| Closed| | Sun., Jan. 1st, Korea Holidays |

| Price| | Free |

| Phone| | 043-222-0357 |

| Web site| | 홈페이지 바로가기 |

| Artist| |

이의성,최병석

|

정보수정요청

|

|

Exhibition Information

MINUS HOURS : '+'rather than '-', On the other side of innovation and revolutionary development Kim Sung-Woo(Curating/MINIUS HOURS Cooperation planner) Today we are entering an era of the fourth industrial revolution with the hope that advanced information and communication technologies will converge into the economy and society as a whole, creating an epochal change in the way life and labor are done. The aspirations and expectations for this age of technological revolution we have seen, which calls for innovative technologies such as the Internet of Things, robotics, virtual reality, big data and artificial intelligence, are quite explosive. The core of the industry is production, and production has been advanced from mechanization to massification and informationization, and now it paints a utopian look with innovative transformations of maximizing efficiency through acceleration of speed and hyper-connected expansion of scope. Though cited as a constant core task at the socio-economic level, this modern reality, which is yet to come, is being replaced by words such as the next generation, the future and affluence. This fever for the future has also become a subject that has often been addressed in the recent culture and art circles. And the linguistic rhetoric that represents expectations rather than concerns has been reshaped again and again into the art form, becoming visible through visual language. Understandably, various cultural and artistic institutions are trying to draw the blueprint for the future that it presents (but unknown) in line with the fourth industrial revolution in a more elegant way in art. The current image of reality, which we create in this interlocking way, processes, promotes, and packages things like thoughts, emotions, and views to transmit our senses. But when I came up with the fact that Utopia is an irreconcilable construction, it should be acknowledged that on the other side of the better world promised by the revolutionary leap-off of these industries, not only psychological discomfort and anxiety, but also realistic-level deficiencies and alienation coexist together. Ivan Illich, an Austrian philosopher, mentions the modernization of poverty in accordance with the development of industry. "Modernized poverty" is what he calls poverty in abundance for those who live on the bounty that industrial productivity has brought, and whose ability to live is cut off. This poverty, he argues, deprives them of the freedom and ability they need to live creatively and act on their own. This exhibition, <MINUS HOURS>, discusses the new helplessness of the present era that arises between this illusion of productivity and abundance. This is to begin with the nature of art itself, to visualize critical questions about art as labor and culture and art industries, or to contemplate the usefulness of art that deviates from the efficiency demanded by society, and to deal with practices that go against maximizing productivity and minimizing time and labor costs. And now, rather than setting the social coordinates at a brilliant future point, they want to measure the present through the missing time and value that have come out of it. It delays investigations such as "innovation" and "revolution" that stick like blind labels to industry and economy, and standing in opposition to the obsessive attitude of expecting maximum efficiency and productivity under economic indicators, it is an act of resisting the formidable speed prevalent in this society, maintaining the byproduct-stacking stance of time, labor, incapacitation and unproductive. Rowa’s work, which comes to face from the outset of the exhibition, takes a macro view of the neo-liberalistic market economic system centered on competition and efficiency. <Frameed Play> is a compilation of the record-breaking footage of a cup-stacking competition, in which players win by performing missions faster than their competitors. However, in the end, the goal they are trying to achieve is nothing but a fruitless act of piling up cups and breaking them down again. This reminds us of the futility of competition in that the painstaking tower-target ends with collapse again, and makes critical reasons for the social structure that builds ranks around the results. <Framed Play> soon leads to the inner <hands of 176>. Scissors, rocks, beams, and three hand gestures appear repeatedly on the screen of each image played in a triangular plot. The 176-handed video is derived from the Internet's social, political, economic and cultural sources, who continue to clash and confront each other and play games without winners and losers. This, in turn, is more maximized by the sound installation task <Losing Game>. The work, which arranged Amy Winehouse’s "Love Is a Losing Game" to repeat the lyrics of "losing game," metaphorically repeats the self-taught structure of contemporary winners, recalling being left out under the guise of "improvement" in society and disappearing pointlessly. Finally, there is <N>, nailed on a wooden board. A closer look at the head of a nail shows the formula ‘3 + 1 X 2 / 2 ? 4’ in the pitch angle (cross, or flat). The number of these formulas and the calculation symbols are followed in order, and the conclusion is '0'. In the end, these enigmatic games that cross Rowa’s work result in zeroes, like the answers given by NNN, which brings us back to the myriad of time, labor, individuals and societies left behind the performance that one development creates. And it reminds us that progress in a society that promises in dramatic language, such as innovation and revolution, in the media is a matter of paying such a price and expense. After all, a huge achievement does not naturally arise under the name of progress, but involves a number of sacrifices, elimination, and fallouts, and the state of ‘zero’ that its balance creates is an attempt to confront it now and again from behind the development of society. Choi Byung-suk's <Pest Control> is an exaggerated system that works for too little a goal. This work exists for the purpose of exterminating vermin, which is hard to imagine in the " bleached" space of an art museum. The museum is willing to advocate a neutral "white space" for the lofty status of work. In this place, where it has authority to see what is certified as art, or even what is not, in an artistic context, it is not allowed to blemish its appearance in addition to those surrounding it. (Under the name of exhibition, the time and labor behind it, in addition to those on the art recognized and visible surface, disappear into the back of the stage.) However, Choi's work begins with the existence of an inextricable pest here and sets up a collection (Pest control-step 1. Collect) - collection (Pest control-step 2. Collection) - incineration (Pest control-step 3. incineration) - disinfection mechanism (Pest control-step 4.perfection) to exterminate it. In fact, the four steps of this system are, in particular, vastly inflated, compared to the goals it is trying to achieve or the actual expectations it is going to achieve. This reminds us of any additional costs caused by market activities, such as environmental pollution in factories and commodity disposal costs, in addition to the explicit costs we pay to receive services in the market. Choi Byung-suk's <Pest control> is, after all, a logically ill-conceived system design that visualizes the time of the labor and process put in for the goal, and even reminds us of externalities such as social costs. After all, the system, which has become bigger in the belly than in the belly, is also a system that maximizes the irony of excessive energy that goes beyond the limit. Kwon Yong-joo presents work that stems from his realistic experience. He is also a writer and exhibition designer. In the first place, he would have chosen to be an exhibition designer who created an exhibition space to continue his work as a writer. The writer, who used to sing "What is the main job and what is the side job?" in <All-around Wall> consisting of a rotating wall and a single-channel video, intersects the separation of life and art and the difference between art and labor, questioning the creation of values and blurring the boundaries of different meanings. And soon he says he expected certain "work" he had been doing to be sublimated into a worthwhile act, leaving some effect on a realistic level. The official title of exhibition designer is created at the institutional level of the museum. This can be said to be a practical hope that the practice of labor and work from a more ethical perspective, transcending personal reasons. There was a belief that ‘providing proof of our values and needs’ could contribute to the creation of a particular profession in the social fabric, as it said in Universal X. However, this soon leads to "no new positions as exhibition technicians and designers have been created within the art institution as expected," and in the end it is forced to remain a "contracting position." Companies outsourcing under the name of management innovation to build an organizational structure that can respond to changes in the market flexibly and quickly and to maximize efficiency. The introduction of outsourcing is aimed at reducing costs, reducing time and improving quality, but at the same time, it has the problem of producing many irregular workers and creating an unstable job environment. In the end, Kwon reminds us that the reality that the art industry guarantees is nothing more than this unstable position of labor, linking the point of field work (all-around wall), the point of exhibition design (difficulty if possible) through computer programs, and the point of intersection of virtual reality and fun (all-around X). Opposite <The Weight of Labor 작업 is located across from these Kwon Yong-ju tasks. In this work, the author aims to measure the time, units and monetary value involved in labor based on the ‘tool’ employed for production activities. Here, tools are agents of physical behavior and processes, materials that embody the value of "production" accepted by society, and are a medium that visualizes the value and purpose of labor. In general economic activity, labor is soon returned to money, but the author puts it in weight. In this act of cutting a tool using the remnants of the other writer, the objection is to record the time taken to make each tool, measure the weight generated during the production process, and record the difference in weight between the first and later. It is the act of labour to reconsider the productivity guaranteed and the value lost from it. Another work, procreation drawing, deals with animal reproductive activities that can be understood as a concept of wealth in terms of production and consumption. From a human-centered perspective, the breeding of livestock, such as property-raising activities, is a reminder of the society's desire to secure and increase labor and productivity through the control and discipline of life. In a slightly different context, <Source Separation Site리포 focuses on a special object called packaging. Packing points to the value of the internal existence it seals, while at the same time only the additional cost of not having any special value in itself. The exterior of the package surrounding it is enlarged and more ostentatiously decorated just to avoid revealing its internal value. And as soon as the original value of the package is revealed, the thin, fine value of the paper is crumpled into garbage. In this work, the wrapper that corresponds to a kind of abandoned workforce is a medium that implies an act that deviates from the center of labor that produces immediate profits at a social level. In addition, the image of crumpled wrapping paper is patterned and put back on paper for packaging, where the author attempts to copy such reconstructed packaging (gees) into a circular form and metaphorize labor that does not produce value in itself. In the end, this work is intended to rethink the value of diverse labor, which, through its packaging, deviates from the productivity centers that exist in our society, including art. Finally, the flat, massive, or voluminous rounds scattered on the floor are Park’s work, <cubbles>. These are borrowed forms from fitness equipment used in fitness centers and at home, as can be easily inferred from their appearance. However, the exaggerated scale and materialism that cannot be found in off-the-shelf products indicate that it is soon out of function. The problem of the form, size and material of an industrialized product is always adopted and applied in the most reasonable and efficient manner in line with its function and purpose. As is the case with most off-the-shelf products, the hardware that corresponds to the surface of the product is structured in a form that produces maximum profit without going against the function and purpose of the product. But the hula hoop, barbell, jimbal, training cone and quartet that make up the <colls> are already dominated by "artistic" objects that simply decorate space in their formative form, with their original function and purpose covered. And the cup (training cone), which is placed on the floor showing off its heavy presence with a hard-looking skin such as a lump of iron, and whose intentions have been blurred by its modified size, soon expands its meaning to another symbol of comparing the body by the time the giant hole (hula hoop) was made. This leads to how the human body is viewed as an industry object under the name of health, and critical recognition of the ‘health’ that the media generates in the form of industry to reach the beautiful body that it calls for. In addition, the accompanying video, "I’m sorry for being born," seeks to unravel the meaning of (art) production, the legitimacy of what exists, and the subject of value giving into the most meaningless things (or things that can’t be found at all). The melodrama, which encompasses the entire image, offers an opportunity to reserve and re-assume its value and conclusions about the most useless, or the most easily forgotten, existence. <MINUS HOURS> requires that you turn your eyes to reality behind tomorrow’s rich, custom-produced promises in line with the industrial cycle. This begins with a macroscopic view of this world, where the balance of production and alienation is created, and takes note of the irony and external effects of systems that have become significantly bloated compared to their goals (Choi Byung-seok), or the ecology of unstable labor markets created for management efficiency (Kwon Yong-ju). And consider art labor and its productivity (reasoning), which are not centered on efficiency, and physical problems (Park Ji-hye) targeted by industrial products. The world in which we live often places greater value on the immediate benefits and effectiveness that arise immediately under the logic of productivity and efficiency. The unfulfilled future does not allow time to face reality under various images and slogans, and is busy panting forward like a fever for the day. Fortunately, art time is the time to call for deep contemplative attention, as Benjamin Walter Benjamin talked about. Rather than focusing on physically exposed outcomes and immediately judging the value of profit, this is a time to move away from the current pace and allow you to face things that are not seen as different scales of value. Therefore, this exhibition proposes to take a step with the "opposition" rather than keeping pace with the trend that continues to accelerate towards the "forward," and calls for measuring where "life"-based labor is located in a manner that goes against the benefits and efficiency pursued by productivity at the industrial level.