| Period| | 2024.01.25 - 2024.03.16 |

|---|---|

| Operating hours| | 10:00 - 18:00 |

| Space| | Perrotin Dosan Park/Seoul |

| Address| | 10, Dosan-daero 45-gil, Gangnam-gu, Seoul, Korea |

| Closed| | Sun, Mon |

| Price| | Free |

| Phone| | 02-545-7978 |

| Web site| | 홈페이지 바로가기 |

| Artist| |

|

정보수정요청

|

|

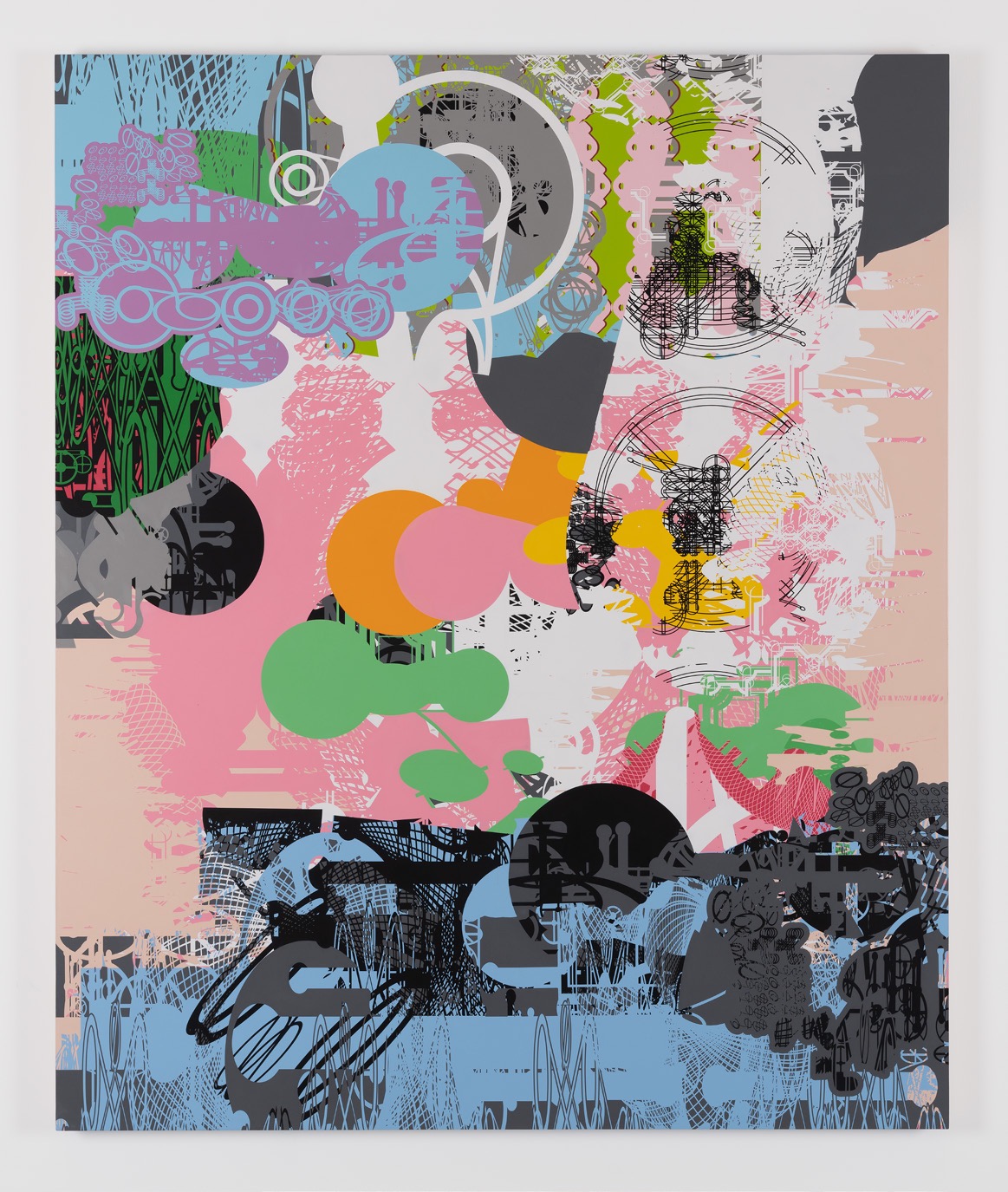

Exhibition Information

Perrotin Seoul is pleased to present Forme d’esprit, a solo exhibition by Sang Nam Lee, an artist who has been working in New York since 1981. Showcasing 13 works that span the artist’s career from the 1990s to 2023, the exhibition will explore Lee’s unique geometric and abstract language accumulated over four decades of artistic oeuvre. "I touch the line between modernism and postmodernism, rationality and irrationality, analog and digital, painting and architecture, art and design. I live in between. Painting makes everything possible. It can hold everything." - Sang Nam Lee Before moving to New York in 1981, Sang Nam Lee took part in many experimental art exhibitions. In 1972 and 1974, Lee exhibited his Window series, utilizing the then-innovative medium of photography, at Indépendants exhibition. He went on to steadily expand his global footprint, showcasing work across a range of events spanning the Daegu Contemporary Art Festival, an experimental mid-1970s Daegu-based art movement, Korea: A Facet of Contemporary Art, 1977 exhibition at the Central Museum of Art in Tokyo, and even the 15th São Paulo Biennial, held in 1979. Indeed, it was an invitation to participate in Korean Drawings Now, a group exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, that brought Lee to New York in 1981. Not long after Lee left for New York, Bahc Yiso (Mo Bahc) also left Korea for the United States. For Lee — then a young man in his twenties — the 1970s was a time of endless experimentation and theoretical questions about painting itself, a period of discovering how own aesthetic and contemplating the anti-traditional methods and mediums of artists like Park Seo-Bo and Lee Ufan through opportunities such as the Indépendants exhibition. In 1981, when Sang Nam Lee first began working there, the New York art scene held no great love for the kind of minimalism and conceptual art he had encountered in Korea. Rather, the buzz then was about German Expressionism, Neo-Expressionism, and paintings by Eric Fischl and David Salle; and so, it was amidst a veritable flood of different concepts, artists, and art institutions that Lee began to explore the bounds of his own artistic language all through the 1980s and into the mid-1990s. From the vantage point of Lee’s return to Korea, beginning with his 1997 exhibition at Gallery Hyundai, this early New York period marked an important turning point in the formation of his work. As alternative independent spaces started proliferating across the city, critical theories of feminist art, Third World art, colonialism, postcolonialism, and postmodernism were beginning to sweep the art world in New York. When Bahc Yiso, with his founding of “Minor Injury” — an alternative space in Brooklyn — in 1985, began actively organizing solo exhibitions of Third World artists long relegated to the margins, circling the realm of identity politics, Sang Nam Lee turned to geometric abstraction in painting to find the answers that he did not find in Seoul. The form of Lee’s images from these early New York years will strike those acculturated to the reproducibility of painting as foreign, a set of alien signs. They appear simultaneously as image, and shape, and form, and sign. Each is composed of geometric elements — point, line, and plane — but they are also enigmatic forms, difficult to pin down: a riddle. During his time in New York, Lee took part in Personal History/Public Address at Bahc Yiso’s Minor Injury and Homeless at Home at Storefront Gallery for Art and Architecture, a show organized by founding director Kyong Park. Through exhibitions like these, the artist’s work was able to break away from the modernist approach of separating the world of painting from the world beyond the frame. For Lee, painting constructs an intertwined worldview in which our living spaces, architectural spaces, and social issues intersect and maintain close relations with one another. Especially during the same period, Lee emphasized the process of phenomenologically re-positioning painting in the context of architectural space, establishing a distinctive mode of "installation painting in situ." His descriptions of "dislocating, twisting, and overlapping," reminiscent of Gilles Deleuze, reveal a process of expanding the understanding of painting itself to include new relationships with architecture, design, and the surrounding space. Furthermore, this relates to the way in which accumulated signs manifest in his paintings, such as numbers, symbols, letters, and codes. And this, in turn, leads to philosophical reflections on the different ways we live our lives, our various entanglements, and, indeed, our very existence. Formally, Sang Nam Lee's work belongs to the category of geometric abstraction, but these works also contain collisions and ruptures in meaning that arise from a constant denial of any fixed relationship between the form and content of the image/sign. From time to time, these cracks can generate a kind of tension and wit — and we come to understand that Lee’s paintings do not reproduce distinct forms. Of course, the shapes we see between images might, at one instant, appear to be an all-encompassing city of mechanical civilization; or a panorama of everyday objects accumulated into multiple layers; or a march of musical notes taking on geometric shapes: themes that reveal the flow of energy in color and form. Color, however, has here departed from the grammar of representation. At times, Sang Nam Lee's signs — like signals from someone else — convey an esoteric, mysterious air. Why does Lee intentionally resist fixing his images in place? Why does he set his forms in motion, slipping and sliding, so that we cannot recognize them? The forms chosen by Sang Nam Lee, turned into signs, are “nomadic beings” that float constantly between here and there, refusing to settle down. When we understand the images in Lee’s work to be signs, they do not then settle down in one place to create a story and build and identity; rather, they roam, nomads unable to root in place, continually connecting and entangling the here with the there. Lee’s signs are not unrelated to his own life and his journey through the various cities in which he has lived. The artist has long shaped himself into a kind of “drifting” being, an existence always on the move. The way Lee’s pieces seem to offer a space of entanglement connecting online and offline; the way it feels natural to draw a connection between his work and artificial intelligence, or self-generated images; and indeed, the way his oeuvre embraces and integrates the extremes of analog and digital writ large: this can all be traced back to the power of the drifting image in Lee’s paintings. The artist’s “drawing diaries,” which he kept for decades, are a record of such floating signs. When Lee’s forms are fixed and his images made legible, Lee returns to the negation of the image — a painterly phase to be navigated once more. When the images created through this process seem at risk of being labeled with meaning, the artist once more sets his images and signs slipping and sliding. While we, as a society, generally understand the fixed meaning of a given image to be what it symbolizes, Sang Nam Lee’s creations function in a manner that is closer to the "allegorical impulse" of postmodern artists and theorists, or “allegory” according to German philosopher Walter Benjamin, or the "obtuse meaning" of Roland Barthes. In rejecting the symbolic meanings inherent in a culture, Lee chooses a mode of thinking that actively denies the primary meanings, stereotypes, and traditions assumed by that culture. This is an approach that enriches meaning, embracing and engaging the diverse ideas of different people and moving away from modes of exclusion. Created in a neo-abstract mode, Lee’s geometric landscape paintings hold the properties and attributes of many disparate cultures and languages as well as ethnicities. The resulting signs are the images he has accumulated over more than four decades. They are more than just shapes; they are compressed landscapes of the artist's mind, revealing the vistas of the cities and sites he has painted, the trajectories and journeys that make up his life. The way in which the artist arrives at the shape of a sign is important, certainly, but in Sang Nam Lee’s work, the process of production itself is also quite unusual. In the earlier works, everything was done by hand — from creating the shape of a prototype to transferring it into the realm of the plane; gradually, however, he began utilizing computers for prototyping, which could then be subjected to a kind of “algorithmic” process to extract more images. The production method, which the artist describes as one of “marquetry” (or inlay), is the result of many distinct processes that include the application of acrylic paint as a base, then a layer of lacquer to that base, followed by sanding and coloring. To Lee, erasing any traces of his actual handiwork is a part of the "labor required to create an artificial, smooth substance." In Lee’s aptly-titled painting 4-fold landscape (2016), images are superimposed and folded to create a new image. Sang Nam Lee’s choice of Forme d’esprit as the title for this present exhibition is a testament to the fact that the forms and signs of his images are not unrelated to the journey, trajectory, and spirit of the mind. The way the artist represents the process of "sensing," with various icons overlapping or even colliding, also recalls the body movements embodied in him practiced at the Judson Dance Theater (an experimental art and avant-garde collective in New York presenting dance, performance art, etc.). By moving their own bodies, viewers encounter — by chance — the icons within the paintings, breaking the remembered forms they know and experiencing the birth of a new image (sign). The work of Sang Nam Lee, in which the artist becomes one with the material itself, requiring the application of countless hours and tireless labor for completion, ultimately reaches a point of resolution in complete opposition to the materiality of the surface itself, which was often the focus of artists practicing Dansaekhwa. Lee does not suppress the riot of color that characterizes the great cities of our day, like New York; nor does she reject the smoothness of the mechanical, minimalist surface. Via New York, Lee has created relational landscape paintings that are distinctly contemporary: geometric, entropic, and thus rhizomatically intertwined, reflecting the lives of his contemporaries as they move and drift between here and there (and this “here” and “there,” after all, aren’t actually assigned to any specific place, are they?). Much as the distance between foreground and background is compressed and vanished in Lee's works, the horizontal temporality of its space serves a key function; meaning that “here” and “there” can easily be transposed to “there” and “here,” refusing to exist in the dynamic of power that is the relation between center and periphery. Sang Nam Lee's paintings, which exist somewhere between analog and digital, modernism and postmodernism, create landscapes of entanglement itself — the kind of entanglement that mediates space, place, and temporality alike. Yeon Shim Chung (Professor, Hongik University) (Source = Perrotin Seoul)