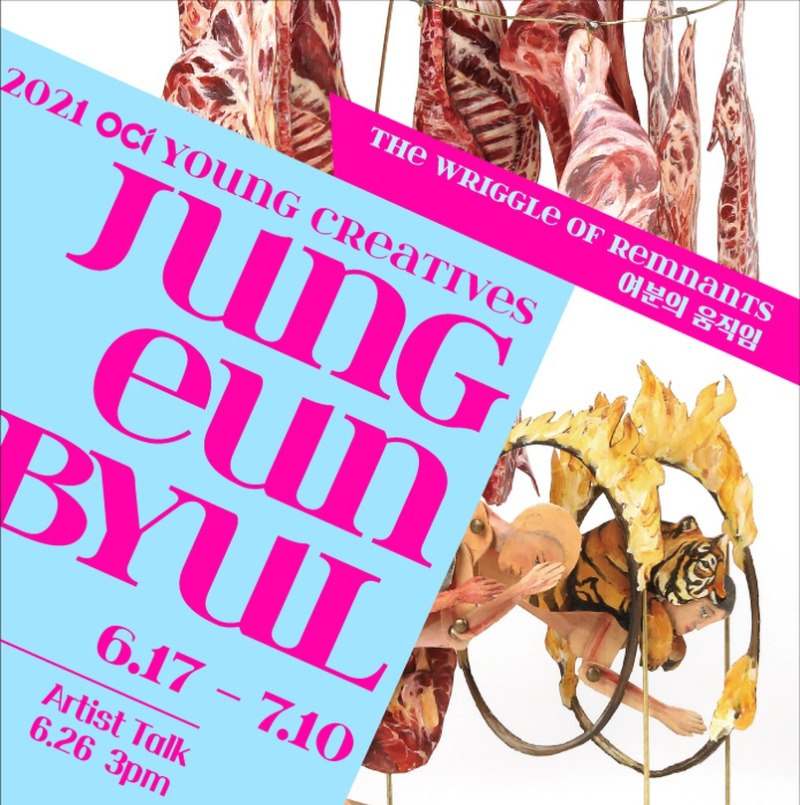

| Period| | 2021.06.17 - 2021.07.10 |

|---|---|

| Operating hours| | 10:00 - 18:00 |

| Space| | OCI Museum of Art/Seoul |

| Address| | 45-14, Ujeongguk-ro, Jongno-gu, Seoul, Republic of Korea |

| Closed| | Sunday, Monday, Holiday |

| Price| | Free |

| Phone| | 02-734-0440 |

| Web site| | 홈페이지 바로가기 |

| Artist| |

정은별

|

정보수정요청

|

|

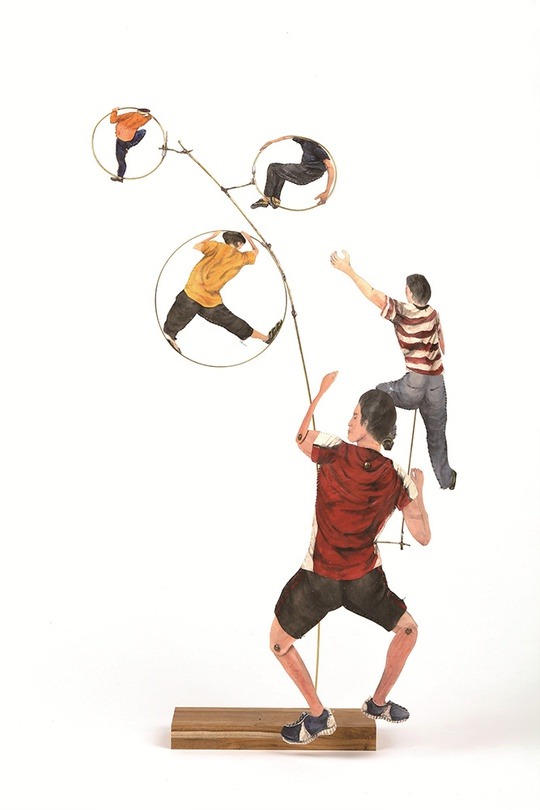

Exhibition Information

The wriggle of remnants Embracing a Large Space As I see the series of paintings, I feel the perspective of mine, stepping onto a large and cohered landscape, and snuggling into the landscape—the inside of the succeeding pictures. My perspective moving from picture to picture and the body that carries the view of mine witness the exploding rupture in the screen and the subtle evanescent that cannot be tracked, in a split second against the heavy pace. It is fine to forget the large landscape just to spot those scenes. If you catch the ruptures gone in a second like a flash by looking deep into the paintings, you wouldn’t even care about the whole scape. 〈The wriggle of remnants〉 by Jung Eunbyul brings up the image of meteor-like short scintillation caused by unnamed remnants and the physical ruptures made by remnants thrown like tiny pieces of rocks. Under the influence of gravity, the dried bouquet dropped the flowers down, lost all its internal vitality, and became stiff like a stuffed animal. The bouquet, been drained and dried, ironically builds its form stubbornly as stuffed animals or fossils—at the moment, Jung bounces her two left fingers to cause a rupture in the “figure of gravity.” The sequence of nine small pieces, (2021), presents the situation. The dried bouquets, which spent a long time to taxidermy their figures against the physical power, are a subject that evokes the precariousness of the solid materials in daily life that Jung has always observed with interests and thoughts. Jung has persistently imagined the moments of the unfamiliar rupture and absence after capturing inherent imperfections of the seemingly unchanging set of things and landscapes that support our lives. shows the facet of figures once maintained by the immense energy of a long time and gravity sinking to the ground and scattering dust all over the air with the action of the small force caused by two fingers in a second. Jung effectively demonstrates movement and transformation in figures with the series of paintings; the slow-motion effect can be detected from the massive and heavy movements moved onto the paintings. Simultaneously, she focuses on the instantaneous rupture of small forces. Jung narrates the moment of the coincidence that encounters the—slow—orbits of the huge external world and the—fast—movement of minor debris by juxtaposing the situations that are conflicting and contrasting to establish the rapid transformation. The paintings of her, like 〈An exceedingly accidental beginning〉, show visual-perceptual introspection on physical things such as multiple temporalities, the magnitude, and speed of power that operate the daily life through the cause-and-effect relationships between the single screen that is overlapped with the movements of fingers and the eight screens of disappearing dried flowers that crumble into the air. It may be one of the significant reasons why she has so contemplated “the way to be seen”—by the viewer—in her works. 〈A gap between to know and to believe〉 (2021) has a similar structure to 〈An exceedingly accidental beginning〉. The plants in the pots neatly placed on the shelf cannot compare with the—stuffed—rose without any wetness or color, but are depicted realistically and elaborately than anything else. It is undoubtful that this plant painting faithfully portrays the peak of life held in a pot. The depiction indicates how much effort she put. However, paradoxically, there is no chance for attention to the familiar forms and vivid colors. By following the subsequent series of paintings, the viewer must face precarious situations and strain their unwary gaze because of the visual-perceptual imperfection of forms beginning to collapse and fading colors. That is it. Just like scouring the sky with eyes wide open to see a meteor falling from the deep dark night, Jung follows the rupture of the moment that will suddenly appear among numerous scenes of daily life built by a huge space and time. Also at 〈An exceedingly accidental beginning〉, our gaze toward the artwork shows the visual-perceptual will to watch or not to watch something in the face of collapsing and fading chaos made by the interference of sudden power, rather than safely stopping in front of the first scene fixed in order as a complete form. I would like to say it is Jung’s unique “drawing-ish thinking” because, in a more comprehensive sense, she shows implications by translating some form of movements into an act of drawing on screens as series of spaces. 〈Bump, and the world is shaken〉 (2021) plays a stage-like role in 〈The wriggle of remnants〉 that demonstrates the power of the entire space. It might be the visual-perceptual effects of individual elements and forms that make up 〈Bump, and the world is shaken〉 that made me coin the term “drawing-ish thinking.” There is an intention to observe the changes and movements in some situations, just as esquisse or rough sketches to complete the picturesque painting. Therefore, there is even an impression that Jung’s artworks have figurative features with a tendency to show the sequential change, the stages of collapse, or the retention at the incompletion stage rather than marked as complete. In that sense, 〈Bump, and the world is shaken〉, in collaboration with author Han Jaeseok at the final set of the work, intuitively shows unfinished or undecided movements using Han’s speaker devices as the source of energy. What is important is the subversive gesture that each figure structurally implies; the gestures suggest the movements of individual forms to consequently provide large and small clues to the multidimensional space of the paintings that lead to the canvases. Take a look at the individual forms that make up 〈Bump, and the world is shaken〉; those fragile and precarious figures finely shaken by the waves of sound and the stuffed landscape surrounded by the huge space like folding screens. Jung repeatedly handles the theme of continuous tensions. By juxtaposing the double values of large and small, sound and fragile, slow and fast, stationary and moving, in and out, she reveals the intention to grasp the incomplete and unsure senses made by it. Simultaneously, the endless subversion and transformation resulted from her actions cannot be overlooked because her attitude of constantly traveling between the pictorial responsibility and the pictorial amusement defends the context of her work that cannot easily be defined by anything. That is to say, Jung has been crossing the frame of painting with her “drawing-ish thinking” and maximize her amusement of self-sufficient hands while renewing the spatial structure of painting at the same time. For her, painting is a medium based on Oriental painting—as an embodied sense. In a position that concludes the movement of the exhibition, we meet 〈When the candle goes out〉 (2021) and face the situation to infer again about “the way to be seen” that Jung has pondered on. She arranged a large sequence of six successive paintings and drew attention to the rows of side-by-side edges. There is a space where subtle movements and faint disappearances build sequential narratives; there is a vast landscape and an implicit of small and enigmatic movements in the gap between the vast landscape and the margins in the space. Paradoxically, the fine rupture seems to embrace the large space, just as the remaining delusion of the viewers who try to face the world of truth by digging into the cliché of realities in front of a few giant landscapes. This may be the series of phenomena in which the media ease of Oriental painting’s worldview be referred to as “The wriggle of remnants” in Jung’s work. Ahn Soyeon, art critic